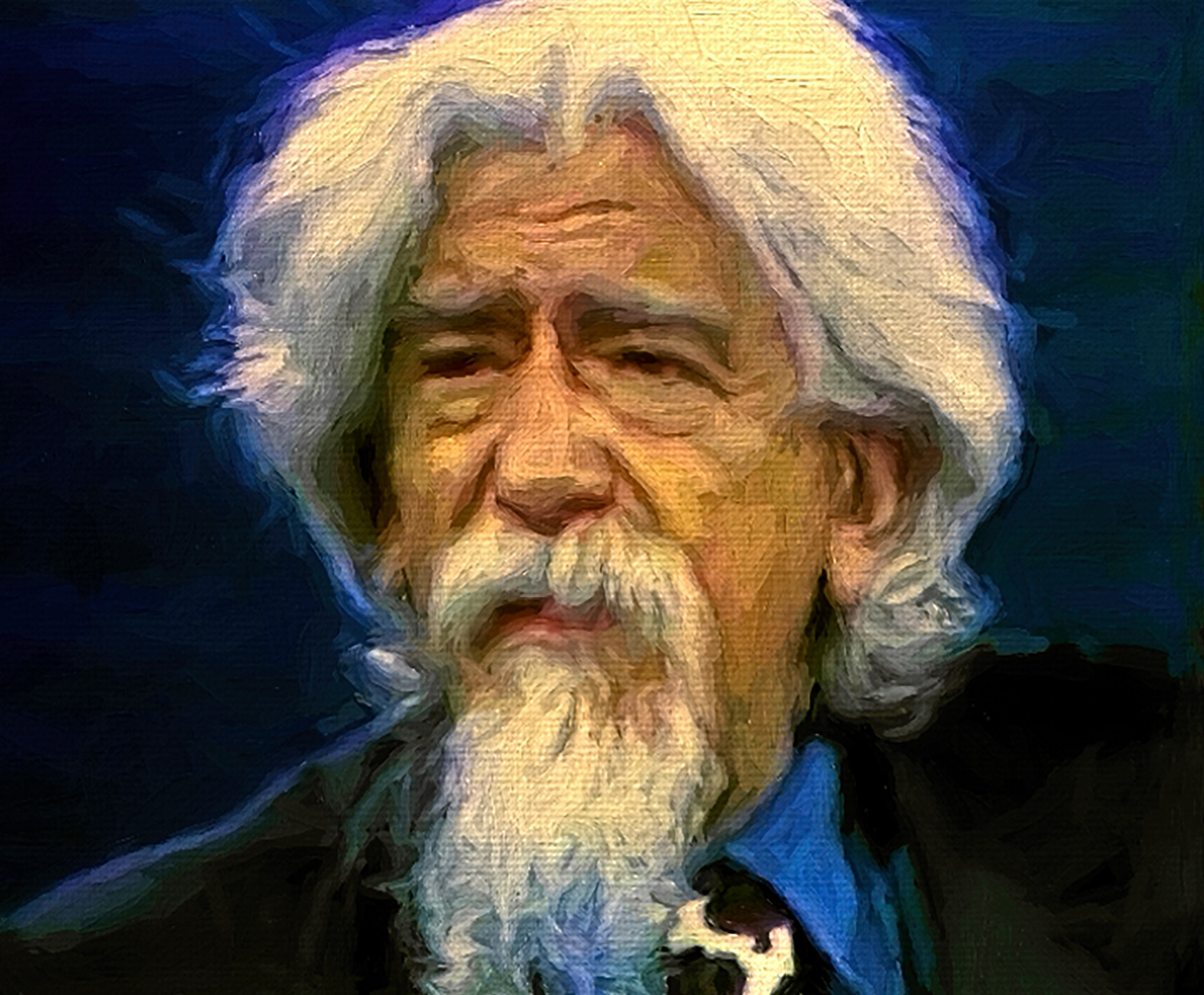

Abraham Joshua Heschel was a Jewish American rabbi, scholar and philosopher who was very active in the U.S. Civil Rights Movement…

… The results of Heschel's wide-ranging studies contributed to the formation of his original philosophy of Judaism, expressed in his two foundational books, Man Is Not Alone (1951) and God in Search of Man (1955). Religion is defined as the answer to man's ultimate questions. Since modern man is largely alienated from reality, which informs genuine religion, Heschel tried to recover the significant existential questions to which Judaism offers answers. This leads to a depth-theology which goes below the surface phenomena of modern doubt and rootlessness and results in a humanistic approach to the personal God of the Bible, who is neither a philosophical abstraction nor a psychological projection, but a living reality who takes a passionate interest in His creatures. The "divine concern" or "divine pathos" is the central category of Heschel's philosophy. Man's ability to transcend his egocentric interests and to respond with love and devotion to the divine demand, to His "pathos" or "transitive concern," is the root of Jewish life with its ethics and observances. The ability to rise to the holy dimension of the divine imperative is at the basis of human freedom. The failures and successes of Israel to respond to God's call constitute the drama of Jewish history as seen from the viewpoint of theology. The polarity of law and life, the pattern and the spontaneous, of keva ("permanence") and kavvanah ("devotion"), inform all of life and produce the creative tension in which Judaism is a way of prescribed and regular mitzvot as well as a spontaneous and always novel reaction of each Jew to the divine reality.

Heschel developed a philosophy of time in which a technical society that tends to think in spatial categories is contrasted with the Jewish idea of hallowing time, of which the Sabbath and the holidays are the most outstanding examples (The Sabbath, 1951). He defined Judaism as a religion of time, aiming at the sanctification of time. In his depth-theology, which is based upon the human being's pre-conceptual cognition, Heschel thought that all humanity has an inherent sense of the sacred; he pleaded for a radical amazement and fulminated against symbolism as a reduction of religion. Instead of advocating a sociological view of Judaism, he highlighted the spirituality and inner beauty of Judaism as well as the religious act, while at the same time rejecting a religious behaviorism without inwardness. Heschel's way of writing is poetical and suggestive, sometimes meditative, containing many antitheses and provocative questions and aims at the transformation of modern man into a spiritual being in dialogue with God.

Underlying all of Heschel's thought is the belief that modern man's estrangement from religion is not merely the result of intellectual perplexity or of the obsoleteness of traditional religion, but rather the failure of modern man to recover the understanding and experience of that dimension of reality in which the divine-human encounter can take place. His philosophy of religion has therefore a twofold aim: to forge the conceptual tools by which one can adequately approach this reality, and to evoke in modern man – by describing traditional piety and the relationship between God and man – the sympathetic appreciation of the holy dimension of life without which no amount of detached analysis can penetrate to the reality which is the root of all art, morality, and faith.

Heschel applied in a number of essays and addresses the insights of his religious philosophy to particular problems confronting people in modern times. He addressed rabbinic and lay audiences on the topics of prayer and symbolism (see his Man's Quest for God, 1954), dealt with the problems of youth and old age at two White House conferences in Washington, and played an active part in the civil rights movement in the U.S. in the 1960s, and in the Jewish-Christian dialogue beginning with the preparations for Vatican Council II. Heschel thought that religious people from various denominations are linked to each other, since "No religion is an island."

Heschel considered himself a survivor, "a brand plucked from the fire, in which my people was burned to death." He also regarded himself as a descendant of the prophets. He was a person who combined inner piety and prophetic activism. He was profoundly interested in spirituality, but an inner spirituality concretely linked to social action, as exemplified by his commitment to the struggle for civil rights in the U.S., by his protests against the Vietnam War, and by his activities on behalf of Soviet Jewry (see i.a. The Insecurity of Freedom: Essays on Human Existence, 1966).